- Home

- William Kennedy

Ironweed (1984 Pulitzer Prize) Page 12

Ironweed (1984 Pulitzer Prize) Read online

Page 12

Helen walked to the church with head bowed. She was picking her steps when the angel appeared (and she still in her kimono) and called out to her: Drunk with fire, o heav’n-born Goddess, we invade thy haildom!

How nice.

The church was Saint Anthony’s, Saint Anthony of Padua, the wonder-working saint, hammer of heretics, ark of the testament, finder of lost articles, patron of the poor and of pregnant and barren women. It was the church where the Italians went to preserve their souls in a city where Italians were the niggers and micks of a new day. Helen usually went to the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception a few blocks up the hill, but her tumor felt so heavy, a great rock in her belly, that she chose Saint Anthony’s, not such a climb, even if she did fear Italians. They looked so dark and dangerous. And she did not care much for their food, especially their garlic. And they seemed never to die. They eat olive oil all day long. Helen’s mother had instructed her, and that’s what does it; did you ever in all your life see a sick Italian?

The sound of the organ resonated out from the church before the mass began, and on the sidewalk Helen knew the day boded well for her, with such sanctified music greeting her at the dawning. There were three dozen people in the church, not many for a holy day of obligation. Not everybody feels obligations the way Helen feels them, but then again, it is only ten minutes to seven in the morning.

Helen walked all the way to the front and sat in the third pew of center-aisle left, in back of a man who looked like Walter Damrosch. The candle rack caught her eye and she rose and went to it and dropped in the two pennies she carried in her coat pocket, all the change she had. The organist was roaming free through Gregorian hymns as Helen lit a candle for Francis, offering up a Hail Mary so he would be given divine guidance with his problem. The poor man was so guilty.

Helen was giving help of her own to Francis now by staying away from him. She had made this decision while holding Finny’s stubby, bloodless, and uncircumcised little penis in her hand. She would not go to the mission, would not meet Francis in the morning as planned. She would stay out of his life, for she understood that by depositing her once again with Finny, and knowing precisely what that would mean for her, Francis was willfully cuckolding himself, willfully debasing her, and, withal, separating them both from what still survived of their mutual love and esteem.

Why did Helen let Francis do this to them?

Well, she is subservient to Francis, and always has been. It was she who, by this very subservience, had perpetuated his relationship to her for most of their nine years together. How many times had she walked away from him? Scores upon scores. How many times, always knowing where he’d be, had she returned? The same scores, but minus one now.

The Walter Damrosch man studied her movements at the candle rack, just as she remembered Damrosch himself studying the score of the Ninth Symphony at Harmanus Bleecker Hall when she was sixteen. Listen to it carefully, her father had told her. It’s what Debussy said: the magical blossoming of a tree whose leaves burst forth all at once. It was the first time, her father said, that the human voice ever entered into a symphonic creation. Perhaps, my Helen, you too will create a great musical work of art one day. One never knows the potential within any human breast.

A bell jingled as the priest and two altar boys emerged from the sacristy and the mass began. Helen, without her rosary to say, searched for something to read and found a Follow the Mass pamphlet on the pew in front of her. She read the ordinary of the mass until she came to the Lesson, in which John sees God’s angel ascending from the rising of the sun, and God’s angel sees four more angels, to whom it is given to hurt the earth and the sea; and God’s angel tells those four bad ones: Hurt not the earth, nor the sea, nor the trees.

Helen closed the pamphlet.

Why would angels be sent to hurt the earth and the sea? She had never read that passage before that she could remember, but it was so dreadful. Angel of the earthquake, who splits the earth. Sargasso angel, who chokes the sea with weeds.

Helen could not bear to think such things, and so cast her eyes to others hearing the mass and saw a boy, perhaps nine, who might have been hers and Francis’s if she’d had a child instead of a miscarriage, the only fertilization her womb had ever accepted. In front of the boy a kneeling woman with the palsy and twisted bones held on to the front of the pew with both her crooked hands. Calm her trembling, oh Lord, straighten her bones, Helen prayed. And then the priest read the gospel. Blessed are they who mourn, for they shall be comforted. Blessed are ye when they shall revile you, and persecute you, and speak all that is evil against you, untruly, for my sake: be glad and rejoice, for your reward is very great in heaven.

Rejoice. Yes.

Oh embrace now, all you millions,

With one kiss for all the world.

Helen could not stand through the entire gospel. A weakness came over her and she sat down. When mass ended she would try to put something in her stomach. A cup of coffee, a bite of toast.

Helen turned her head and counted the house, the church now more than a third full, a hundred and fifty maybe. They could not all be Italians, since one woman looked rather like Helen’s mother, the imposing Mrs. Mary Josephine Nurney Archer in her elegant black hat. Helen had that in common with Francis: both had mothers who despised them.

It was twenty-one years before Helen discovered, folded in a locked diary, the single sheet of paper that was her father’s final will, never known to exist and written when he knew he was going to kill himself, leaving half the modest residue of his fortune to Helen, the other half to be divided equally between her mother and brother.

Helen read the will aloud to her mother, a paralytic then, nursed toward the grave for ten years by Helen alone, and received in return a maternal smile of triumph at having stolen Helen’s future, stolen it so that mother and son might live like peahen and peacock, son grown now into a political lawyer noted for his ability to separate widows from their inheritances, and who always hangs up when Helen calls.

Helen never got even with you for what you, without understanding, did to her, Patrick. Not even you, who profited most from it, understood Mother’s duplicitous thievery. But Helen did manage to get even with Mother; left her that very day and moved to New York City, leaving brother dear to do the final nursing, which he accomplished by putting the old cripple into what Helen likes to think of now as the poorhouse, actually the public nursing home, and having her last days paid for by Albany County.

Alone and unloved in the poorhouse.

Where did your plumage go, Mother?

But Helen. Dare you be so vindictive? Did you not have tailfeathers of your own once, however briefly, however long ago? Just look at yourself sitting there staring at the bed with its dirty sheets beckoning to you. Your delicacy resists those sheets, does it not? Not only because of their dirt but because you also resist lying on your back with nothing of beauty to respond to, only the cracked plaster and peeling ceiling paint; whereas by sitting in the chair you can at least look at Grandmother Swan, or even at the blue cardboard clock on the back of the door, which might help you to estimate the time of your life: WAKE ME AT: as if any client of this establishment ever had, or ever would, use such a sign, as if crippled Donovan would ever see it if they did use it, or seeing it, heed it. The clock said ten minutes to eleven. Pretentious.

When you sit at the edge of the bed in a room like this, and hold on to the unpolished brass of the bed, and look at those dirty sheets and the soft cocoons of dust in the corner, you have the powerful impulse to go to the bathroom, where you were just sick for more than half an hour, and wash yourself. No. You have the impulse to go to the genuine bath farther down the hall, with the bathtub where you so often swatted and drowned the cockroaches before you scrubbed that tub, scrub, scrub, scrub. You would walk down the hall to the bath in your Japanese kimono with your almond soap inside your pink bathtowel and the carpets would be thick and soft under the soft soles of your slippers, whi

ch you kept under the bed when you were a child; the slippers with the brown wool tassel on the top and the soft yellow lining like a kid glove, that came in the Whitney’s box under the Christmas tree. Santa Claus shops at Whitney’s.

When you really don’t care anymore about Whitney’s, or Santa Claus, or shoes, or feet, or even Francis, when that which you thought would last as long as breath itself has worn out and you are a woman like Helen, you hold tightly to the brass, as surely as you would walk down the hall in bare feet, or in shoes with one broken strap, walk on filthy, threadbare carpet and wash under your arms and between your old breasts with the washcloth to keep down the body odor, if you had anyone to keep down the odor for.

Of course Helen is putting on airs with this thought, being just like her mother, washing out the washcloth with the cold water, all there is, and only after washing the cloth twice would she dare to use it on her face. And then she would (yes, she would, can you imagine? can you remember?) dab herself all over with the Madame Pompadour body powder, and touch her ears with the Violet de Paris perfume, and give her hair sixty strokes that way, sixty strokes this way, and say to her image in the mirror that pretty is as pretty does. Arthur loved her pretty.

Helen saw a man who looked a little bit like Arthur, going bald the way he always was, when she was leaving Saint Anthony’s Church after mass. It wasn’t Arthur, because Arthur was dead, and good enough for him. When she was nineteen, in 1906, Helen went to work in Arthur’s piano store, selling only sheet music at first, and then later demonstrating how elegant the tone of Arthur’s pianos could be when properly played.

Look at her sitting there at the Chickering upright, playing “Won’t You Come Over to My House?” for that fashionable couple with no musical taste. Look at her there at the Steinway grand, playing a Bach suite for the handsome woman who knows her music. Look how both parties are buying pianos, thanks to magical Helen.

But then, one day when she is twenty-seven and her life is over, when she knows at last that she will never marry, and probably never go further with her music than the boundaries of the piano store, Helen thinks of Schubert, who never rose to be anything more than a children’s music teacher, poor and sick, getting only fifteen or twenty cents for his songs, and dead at thirty-one; and on this awful day Helen sits down at Arthur’s grand piano and plays “Who Is Silvia?” and then plays all she can remember of the flight of the raven from Die Win terreise.

The Schubert blossom,

Born to bloom unseen,

Like Helen.

Did Arthur do that?

Well, he kept her a prisoner of his love on Tuesdays and Thursdays, when he closed early, and on Friday nights too, when he told his wife he was rehearsing with the Mendelssohn Club. There is Helen now, in that small room on High Street, behind the drawn curtains, sitting naked in bed while Arthur stands up and puts on his dressing gown, expostulating no longer on sex but now on the Missa Solemnis, or was it Schubert’s lieder, or maybe the glorious Ninth, which Berlioz said was like the first rays of the rising sun in May?

It was really all three, and much, much more, and Helen listened adoringly to the wondrous Arthur as his semen flowed out of her, and she aspired exquisitely to embrace all the music ever played, or sung, or imagined.

In her nakedness on that continuing Tuesday and Thursday and unchanging Friday, Helen now sees the spoiled seed of a woman’s barren dream: a seed that germinates and grows into a shapeless, windblown weed blossom of no value to anything, even its own species, for it produces no seed of its own; a mutation that grows only into the lovely day like all other wild things, and then withers, and perishes, and falls, and vanishes.

The Helen blossom.

One never knows the potential within the human breast.

One would never expect Arthur to abandon Helen for a younger woman, a tone-deaf secretary, a musical illiterate with a big bottom.

Stay on as long as you like, my love, Arthur told Helen; for there has never been a saleswoman as good as you.

Alas, poor Helen, loved for the wrong talent by angelic Arthur, to whom it was given to hurt Helen: who educated her body and soul and then sent them off to hell.

Helen walked from Saint Anthony’s Church to South Pearl Street and headed north in search of a restaurant. She envisioned herself sitting at one of the small tables in the Primrose Tea Room on State Street, where they served petite watercress sandwiches, with crusts cut off, tea in Nippon cups and saucers, and tiny sugar cubes in a silver bowl with ever-so-delicate silver tongs.

But she settled for the Waldorf Cafeteria, where coffee was a nickel and buttered toast a dime. Discreetly, she took one of the dollar bills out of her brassiere and held it in her left fist inside her coat pocket. She let go of it only long enough to carry the coffee and toast to a table, and then she clutched it anew, a dollar with a fifteen-cent hole in it now. Eleven-eighty-five all she had left. She sweetened and creamed her coffee and sipped at it. She ate half a piece of toast and a bite of another and left the rest. She drank all the coffee, but food did not want to go down.

She paid her check and walked back out onto North Pearl, clutching her change, wondering about Francis and what she should do now. The air had a bite to it, in spite of the warming sun, driving her mind indoors. And so she walked toward the Pruyn Library, a haven. She sat at a table, shivering and hugging herself, warming slowly but deeply chilled. She dozed willfully, in flight to the sun coast where the white birds fly, and a white-haired librarian shook her awake and said: “Madam, the rules do not allow sleeping in here,” and she placed a back issue of Life magazine in front of Helen, and from the next table picked up the morning Times-Union on a stick and gave it to her, adding: “But you may stay as long as you like, my dear, if you choose to read.” The woman smiled at Helen through her pince-nez and Helen returned the smile. There are nice people in the world and sometimes you meet them. Sometimes.

Helen looked at Life and found a picture of a two block-long line of men and women in dark overcoats and hats, their hands in their pockets against the cold of a St. Louis day, waiting to pick up their relief checks. She saw a photo of Millie Smalls, a smiling Negro laundress who earned fifteen dollars a week and had just won $150,000 on her Irish Sweepstakes ticket.

Helen closed the magazine and looked at the newspaper. Fair and warmer, the weatherman said. He’s a liar. Maybe up to fifty today, but yesterday it was thirty-two. Freezing. Helen shivered and thought of getting a room. Dewey leads Lehman in Crosley poll. Dr. Benjamin Ross of Albany’s Dudley Observatory says Martians can’t attack earth, and adds: “It is difficult to imagine a rocketship or space ship reaching earth. Earth is a very small target and in all probability a Martian space ship would miss it altogether.” Albany’s Mayor Thacher denies false registration of 5,000 voters in 1936. Woman takes poison after son is killed trying to hop freight train.

Helen turned the page and found Martin Daugherty’s story about Billy Phelan and the kidnapping. She read it and began to cry, not absorbing any of it, but knowing the family was taking Francis away from her. If Francis and Helen still had a house together, he would never leave her. Never. But they hadn’t had a house since early 1930. Francis was working as a fixit man in the South End then, wearing a full beard so nobody’d know it was him, and calling himself Bill Benson. Then the fixit shop went out of business and Francis started drinking again. After a few months of no job, no chance of one, he left Helen alone. “I ain’t no good to you or anybody else,” he said to her during his crying jag just before he went away. “Never amounted to nothin’ and never will.”

How insightful, Francis. How absolutely prophetic of you to see that you would come to nothing, even in Helen’s eyes. Francis is somewhere now, alone, and even Helen doesn’t love him anymore. Doesn’t. For everything about love is dead now, wasted by weariness. Helen doesn’t love Francis romantically, for that faded years ago, a rose that bloomed just once and then died forever. And she doesn’t love Francis as a companion,

for he is always screaming at her and leaving her alone to be fingered by other men. And she certainly doesn’t love him as a love thing, because he can’t love that way anymore. He tried so hard for so long, harder and longer than you could ever imagine, Finny, but all it did was hurt Helen to see it. It didn’t hurt Helen physically because that part of her is so big now, and so old, that nothing can ever hurt her there anymore.

Even when Francis was strong he could never reach all the way up, because she was deeper. She used to need something exceptionally big, bigger than Francis. She had that thought the first time, when she began playing with men after Arthur, who was so big, but she never got what she needed. Well, perhaps once. Who was that? Helen can’t remember the face that went with the once. She can’t remember anything now but how that night, that once, something in her was touched: a deep center no one had touched before, or has touched since. That was when she thought: This is why some girls become professionals, because it is so good, and there would always be somebody else, somebody new, to help you along.

But a girl like Helen could never really do a thing like that, couldn’t just open herself to any man who came by with the price of another day. Does anyone think Helen was ever that kind of a girl?

Ode to Joy, please.

Freude, schöner Götterfunken,

Tochter aus Elysium!

Helen’s stomach rumbled and she left the library to breathe deeply of the therapeutic morning air. As she walked down Clinton Avenue and then headed south on Broadway, a vague nausea rose in her and she stopped between two parked cars to hold on to a phone pole, ready to vomit. But the nausea passed and she walked on, past the railroad station, until the musical instruments in the window of the Modern Music Shop caught her attention. She let her eyes play over the banjos and ukuleles, the snare drum and the trombone, the trumpet and violin. Phonograph records stood on shelves, above the instruments: Benny Goodman, the Dorsey Brothers, Bing Crosby, John McCormack singing Schubert, Beethoven’s “Appassionata.”

Riding the Yellow Trolley Car: Selected Nonfiction

Riding the Yellow Trolley Car: Selected Nonfiction Changó's Beads and Two-Tone Shoes

Changó's Beads and Two-Tone Shoes Ironweed

Ironweed The Ink Truck

The Ink Truck Billy Phelan's Greatest Game

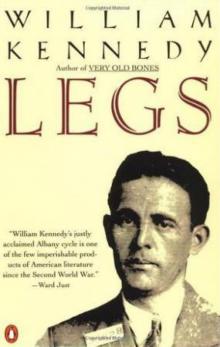

Billy Phelan's Greatest Game Legs

Legs Very Old Bones

Very Old Bones The Last Mission

The Last Mission The Flaming Corsage

The Flaming Corsage Roscoe

Roscoe Quinn's Book

Quinn's Book Ironweed (1984 Pulitzer Prize)

Ironweed (1984 Pulitzer Prize) Riding the Yellow Trolley Car

Riding the Yellow Trolley Car Legs - William Kennedy

Legs - William Kennedy