- Home

- William Kennedy

The Ink Truck Page 3

The Ink Truck Read online

Page 3

“Watch out for the pooka in there.”

“You did bring that hairy thing back. I’ll get rid of it.”

She rifled the drawer of an end table for incense and lit it in an Oriental ashtray. She put the tray on the bedroom floor, opened the room’s window and closed its door, then rechecked all the other rooms.

“Grace and I are at an ending,” Bailey said to Rosenthal. “Our abstractions have become mutually exclusive. There was a time when I sensed that I was divinely favored in discovering Grace because life took on a primitive tone with her, and I’ve always been drawn back to primitive times. With her I felt I’d reached some essential level of behavior, had plunged beneath the crust of sophistication. But it was just another deception, another trap set by the cult of simplicity. I’m no more pure animal than I am pure spirit. What I am, Rosy old man, is a fuck-up. A man people see as a noble boob, a worthy sucker. Quite an image, eh? But I’m out to change all that. I’m heading for new depths. No more fresh starts for Bailey. I’m after mutation now, lopping off parts till the species is as slick and streamlined as a buttered bullet. Eventually I may be able to sell myself to a freak museum as the Transmogrified Man. He cut out his vital parts and fed the birds and the sewers. He opened his veins and dribbled out his blood to thirsty pigs. And he sold his brain to raise funds for a fashionable supermarket. What you see before you, ladies and gentlemen, is the vile corpse. Note that it has petrified ears, vulcanized genitals and a calcified liver. Proceeds from this exhibition will go to the former owner, who has since become an anopheles mosquito.”

Grace came out of the bedroom in time to hear the last of Bailey’s comments.

“You were always a mosquito,” she said.

“You know, don’t you,” Bailey said to her, “that the ginger ale is nowhere near the meat counter.”

Grace’s eyes pulsed. Her eyebrows arched.

“He sees me through the mirror,” she said.

“Furthermore, I recognize your handwriting. The way you cross your t’s gives you away.”

She stared out of a face slowly giving way to defeat.

“Treason drains women of their sexuality,” Bailey told her. “It’s not the same as infidelity. It’s only a matter of weeks before your tits turn to marble.”

Grace wheeled around, snatched the casserole off the kitchen stove and poured it over Bailey’s overcoat on the sofa. Then she threw the pan, hitting his forehead and opening a vertical cut. Bailey twisted her arm behind her, lifted her skirt with his free hand and sat her down on the steaming food.

“This, of course,” he told Rosenthal, “spoils our lunch.”

Rosenthal cleared his throat politely and picked up his coat. Bailey took another coat from a closet, twirled his muffler once around, and they moved gingerly out of the room and down the stairs into the sunlight.

“Did you read my column?” Bailey asked as they walked along the snowy street.

“Unusual, I’d call it. Will your editor approve?”

“I’ve modeled my pooka after him. A soulful drunk named Fagin.”

“Well, your readers, then. It’s a jazzy column, but you’ve got to admit it’s also pretty nutsy.”

“My readers are loyal,” Bailey said. “If I’m nutsy it’s not a problem for them.”

“A nice arrangement,” Rosenthal said.

When they entered the Guild room Rosenthal went to his desk and Bailey, with a solemn look, sat in his chair. As always when he came into the room, he felt a pinch of joy, a twinge of doom. Now doom stuck a rod in his belly, shooting agony-to-come through him. Once again we must go tilting, each in his own way. The Bailey way was not the Jarvis way. A fuss for Jarvis. But the truck driver in Fobie’s had painted a dark vision in Bailey’s imagination: spilled ink. The driver knew how to pull the pin on an ink truck, let the black blood of the company flow over the street. The joy of such a vision. Bailey trembled from it. But would it fruit out? What difference would it make?

Bailey stared at the bulletin board. He saw the new report from Jarvis spiked atop all the others. Oh, no, he wouldn’t read it. He was too full of good things, vicious things, to let Jarvis spoil the mood. He sat quietly, calmed by the potential of his thoughts, comforted by the familiar contours of chair and wall. His eyes turned once again, O inescapable ritual, to the photo of Rosenthal, Jarvis, Irma, himself and others long gone, taken the first night of the strike when they all so enthusiastically walked off the job. What joy on those faces of last year! What radiance! What anticipation! No enraptured face of childhood could ooze innocence more than those happy strikers. But now innocence was gone. In the days that followed that singular night, scores of Guildsmen trooped through the Guild room in snowboots, ski clothes, thermal jackets, fur caps. They dropped paper cups and the ashes of thousands of cigars and cigarettes on the unvarnished floor. They consumed untabulated gallons of donated coffee from Fobie’s (Fobie revoked his donation after two months, claiming hardship). New camaraderies were established among the members, many of whom had never before communicated. They settled into particular corners of the room, favorite chairs; and the whole Guild room took on a fixed appearance that never changed. Lists of scabs and strikebreakers hung on the wall, long out of date, for there had been a heavy turn over of scab labor. Memos on committees caught dust, as did cartoons spoofing company aides and early Guild optimism. The letter from Adam Popkin, the third alternate delegate of the International Guild, sent after the first two weeks of futile picketing and negotiations, still mocked its readers with its capital letters and fading red underlines. Popkin wrote: “I salute you all with the words of Alexandre Dumas the elder, who said: ‘All human wisdom is summed up in two words—wait and hope.’ I believe that no greater message exists.” Popkin’s letter grew yellow beside letters of encouragement from other unions. No one moved anything anymore. Nothing changed. There was no disorderly crowd anymore, no chaotic anger, no happy banter. Bailey, never bored with this condition, always mystified by it, took comfort from the emptiness, the fixed quality, preferred it to that formless clot of old.

“I forgot to tell you,” Rosenthal said. “Irma quit.”

Bailey looked up, stared at Rosenthal, took off his hat. Rosenthal told him the story of his conversation with Francie. Gongs clanged, sirens wailed in Bailey’s head. Irma is on fire.

“Eppis, you say?”

“The same,” said Rosenthal.

“Have to set her straight, poor girl; probably gone mad. I’ll call her and give aid and comfort. Is that or is that not an idea? You straw. You Jew hero. You sliver. Am I right, or would you leave the poor girl alone?”

“I hate to see her go. She’s our last contact with sex.”

“You circumcised pig. Just because Irma has mountains like the Alps, a valley like the Rhine and the lips of a queen bee, you forget she has a mind. Curb your Semitic dangle, Rosenthal. Remember there’s more to life than humpybumps.”

Bailey telephoned and identified himself as a representative of the Sundown Burial Squadron, but Irma recognized his voice immediately.

“I’m through,” she said. “Don’t try to wheedle me back.”

“I just want your reasons. What did it?”

“Easy. I stopped kidding myself we’d ever go back to work. I hate that Guild room and that phony picket line. I was even getting to hate you and Rosenthal. You and your damn old endurance, your rotten nobility.”

“But the straw, lovey, what was the straw?”

“The hairy wart on Jarvis’ chin.”

“It’s his best feature.”

“I kept getting the urge to cut it off with a scissors. I kept thinking: If I cut it off we’ll go back to work. Yesterday I picked up the scissors.”

“We’ll miss you, dovetail.”

“Mutualwise, me too.” She paused, then through a whimper added: “See ya around the campus. And don’t take any wooden pickets, you dumb jerks. Dumb, dumb, dumb. Oh!”

She was in tears.

&nbs

p; “She thinks she won,” Bailey said to Rosenthal as he hung up. “She thinks she’s dead at last. At ease. First she called the undertaker and now she’s crying over her own corpse, worrying about us from the next world.”

He buttoned his coat, twirled his muffler, covered his great crop of wiry black hair with his cossack hat.

“Doughnuts at eight,” Rosenthal said as Bailey strode out.

When he stepped across her threshold, Irma licked his cheek, as a cat kisses after it bites.

“You bastard,” she said. “What are you after?”

They were lovers after the strike exploded. He rubbed up against her at Guild meetings, walked with her on the picket line. She talked to him of meditations at sunset, of Robert Frost and Bette Davis. He found out she wore medium Kotex and thought of herself as a squirrel: bushy-tailed nut collector. Bailey took that two ways. Irma said he was right to do that.

“Kiddo, I don’t believe what you said on the phone. You didn’t tell all.”

“I knew you’d say that,” Irma said. “As soon as you came in I knew why you were here.”

“Irma full of eyes.”

“Sometimes I can’t stand to look at you.”

“Does it eat you I’m not as heroic as I look?”

“Who said you looked heroic?”

“You did. Months ago in the time when we worried over moon phases.”

“I watch you,” she said, “and you don’t shatter. You never shatter. Bailey’s not fragile. He’ll never break. But I see you erode. I see your eyes wander when they used to be steady. I hear your talk fuzz over like a lawn gone to weeds. Poor Bailey, I say. Poor Bailey. You think I can hang around pitying you?”

“Cross your legs like you used to.”

“No.”

“Do you know that I love you now?” he said.

Irma laughed with luxurious pleasure, without mockery. Bailey saw beautiful, rounded flesh: a soft, white inner tube: no bones: only a great, pliant whiteness.

“I love you too, bubbykins,” she said.

She mixed the drinks and raised her bourbon in a toast to their love. Both had professed it when it was only gilded affection, but after the settling in, Irma backed away from Bailey, the ogre-souled outlaw. Scab lifter. Garter snapper. Titty pincher. Oh, Bailey, you dirty bird. He burned her ears with his language, he scorched her heart with his hot love. Oh you Bailey. Irma backed off. She’s no animal. She’s a thirty-four-year-old career girl with a clean heart. It was lovely, Bailey, but after all, you’ve got Grace. Irma quested for reality too. And you’re taken, Bailey. You’re a career striker, and you’re taken.

“How’s Grace?” Irma asked him.

“She’s conventionally ill,” Bailey said.

“Oh, I’m sorry.”

“It’s chronic now. Don’t feel bad. Grace is a brick about it.”

“What is it?”

“The madness. It’s on her.”

“Oh, I’m sorry.”

“We all have our crosses,” Bailey said.

Lust crept up Bailey’s pantleg and tickled him. He wondered about its cause, conjectured on Irma’s stockings and her probable garter belt as catalysts, for he knew her chiefly as a ski-pants type in the filthy winter of the early strike. And later, in the springtime, when she was no longer his and had reverted to skirts (was she fending off the winter cold or the Bailey heat with those pants, now that he thinks of it?), he didn’t pay much attention. But now the time of Irma’s pantslessness had arrived. Bailey looked at her beautiful curve of soft black hair across her forehead, her sweet and simple smile that deceptively covered her toughness. He studied her, thinking: Go quietly, don’t push the girl. After all, she’s engaged. Let magic ignite the dust. But he didn’t wait. The bourbon had loosened his tongue.

“Do you understand it? I’m not sure I do.”

“What, bubie? Your love?”

“It’s so quiet. It goes on even without you.”

“Oh, what glop, Bailey. I never knew you to be sentimental.”

He smiled, knowing her to be quite sentimental, and slid his hand up her nylon until he touched flesh. He stroked it gently.

“What are you after, a little massage to perk up the afternoon, or the whole works?”

“Whatever you’re prepared to give,” he said.

“What kind of a son of a bitch are you, coming in here like this and testing me? You want to tie it all in, don’t you? Love, the Guild, sex, resistance, and rescuing the damsel.”

“I didn’t organize my motives.”

“The hell you didn’t. Rub Irma’s leg. Aladdin and his magic friction machine. She’ll come back. She’ll get the meaning.”

“I see you drifting off, and I want to stop that. But if you’re dead, I want to know it. When I lose what I love, I want full reality.”

“How delightfully absurd of you to say that,” Irma said. She paced and smoked and smirked. Bette Davis-style, Bailey noted. “It really does betray you, you know. On the march to sweet reality. You wouldn’t know the real thing if it walked up and grabbed you by the fanny.” She shook her head, tossed her hair. “Incredible how you believe we’re all committed to that stupid strike. You sound like my aunt telling me it’ll end soon because she had a novena said. Well, I don’t have that kind of faith. I refuse to go on believing impossible things are possible. I want to be alive during my life.”

“Is that why you took up with the undertaker?”

“He pets me, he feeds me, he gives me things. So what if he smells of formaldehyde? I feel normal with him. What did you ever give me?”

“Nothing at all. I took from you steadily.”

Irma sat on the sofa across the room and stared at Bailey. What should a girl do with a bastard like Bailey? See him smile. See him leer. Him and his heavyweight crotch. I got over him. I don’t need him. The hell with him. She said. Then nostalgia crept into her silence and she crossed her legs in the old way. But certain types of behavior are not necessarily what they seem. What Irma decided to do in the moments immediately following was to carry a relationship to its conclusion. She viewed it as punctuation: nostalgic and funereal. Bang, Bailey. You’re dead.

The ink truck bled of its ink grew larger as Bailey thought of it. A gesture at last that would be more than a gesture. It would be the transfiguration of a protest. He would be done with the mortifying slouch of the timid piss ant. Something moved in his center, urging itself upward from the grave. Seeds. Transfigured. Up, up! The crust of the grave began to crack. Isn’t it grand what a little call to adventure can do for you, Bailey. Does Bailey love a challenge? Do eggsuckers suck eggs?

He entered the Guild room, sat once again, stared at the photo once again, felt at ease in old contours once again, was swept over with joy, doom, nostalgia and rancor once again, but with a difference: Black ink covered all doom, ebony beautiful. The viscous gook swamped all piss ants. The stink of hot life drove away the poops, suffocated the finks. Bailey giant-stepped through the mire in the hip boots of a rubbery spirit, inhaling the fumes that polluted the lungs of all but the fittest. Up, up, seeds. Up through the black crust. Up!

“We have a volunteer,” Rosenthal told him, and Bailey looked at the stranger, a curlytop youth, cultivated torso, cocksure young bear swaggering with collegiate improvidence, shorn of innocence, cloaked in early wisdom. I know the score, said the collegian’s face.

“His name is Deek, and he wants to join the Guild.”

Bailey smiled at that. Now that he’s wise he wants to be a hero.

“He’s been reading protest literature and he says our strike is the only thing around that grabs him.”

Sad for you, young bear. There are no more heroic protests. No more heroes. Chivalry is even dead as a memory. Now the cycle is so complete that the damsels are out with their lances, protecting the men. Mother Irma, Dame Irma, protectress, gone from us. Our last touch with unified concubinage, sis, mom and Miss Prim, total female, gone.

“This is Bailey, Deek.

Our prize bull. He’ll tell you about the strike, won’t you, Bailey?” Rosenthal continued with the phone calls.

“I like you guys,” Deek said, pushing out a sophisticated lip. “The way you buck the odds. My father sells ads for the company and talks about you all the time. He says you’re all crazy. He won’t even come near this block. He says one of you’s got a sniper-scope BB pistol and that you take pot shots at company people. That’s cool.”

“You’re not a spy, are you?” Bailey inquired. “The company hardly needs another spy. They infiltrated us months ago, and now they have the gypsies.”

“I’m no spy. My father’d flip if he knew I was here.”

“Tell him about our demands,” Rosenthal said. “That’s what he wants to know.”

“Tell the young man our demands,” Bailey said. “Of course. Tell the young man the secret of the pomegranate. All right. We began asking for $292 a week, not a lordly sum in a time when expense-account thieves live their lives without ever touching their salaries. Yet $292 was far more than the company would give. What’s more, they knew we weren’t out for money, which armed them. We talked about it over the table. We readjusted, compromised. I was our negotiator in those days, having regular conferences with Stanley, the company man. Stanley often confounded me by knowing our proposals in advance: those spies in our ranks, of course, selling us to the devil. But it mattered little. When I tried for a wage raise with a surprise offer to cut back on paid holidays, Stanley would counter with abolition of paid vacations. The low point of my time came when I offered a return to the prestrike status quo in return for the right to charge lunches at the company coffee shop. When Stanley refused this I knew we were in for a bad time. Seven months of strike were already gone. Currently the company stipulates that no strikers be permitted to eat in the lunchroom when the strike ends.

“Jarvis took over when I gave up the mastermind role. But ever since he agreed to a forty-percent salary cut below prestrike levels, his grip on reality has weakened. We understood the depth of his distraction last month when he set up a seafood luncheon meeting with Stanley and tried to send Rosenthal to the pet shop to buy clams. At the moment, Jarvis is still our only contact with the company. Labor lawyers have abandoned us as hopeless, arbitrators have advised us to seek new professions, politicians have found no reason to even recognize our existence now that our position is so weak and our number so small. Jarvis perseveres and Stanley sometimes deigns to meet with him, and we will survive, I presume, as long as the International Guild continues to recognize through its weekly dole that we got into this thing through their original organizational efforts. But when the dole goes, so go we. And until that bleak tomorrow we live on the edge of possibility, believing some white bird of circumstance will one morning light on our shoulders and whisper the secrets of transcendence into our ears. Jarvis negotiates with all the strength in him, then sends in his reports. We avoid reading them since they only spur us to new depressions. Our manner, in a word, is aloof, perhaps even a bit royal.

Riding the Yellow Trolley Car: Selected Nonfiction

Riding the Yellow Trolley Car: Selected Nonfiction Changó's Beads and Two-Tone Shoes

Changó's Beads and Two-Tone Shoes Ironweed

Ironweed The Ink Truck

The Ink Truck Billy Phelan's Greatest Game

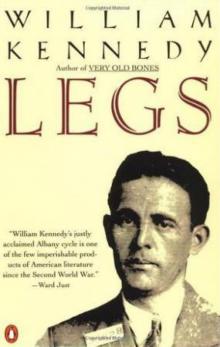

Billy Phelan's Greatest Game Legs

Legs Very Old Bones

Very Old Bones The Last Mission

The Last Mission The Flaming Corsage

The Flaming Corsage Roscoe

Roscoe Quinn's Book

Quinn's Book Ironweed (1984 Pulitzer Prize)

Ironweed (1984 Pulitzer Prize) Riding the Yellow Trolley Car

Riding the Yellow Trolley Car Legs - William Kennedy

Legs - William Kennedy